The Straightification of Nick Carraway

“The Great Gatsby” musical fails to adapt the original’s most compelling aspects

In my younger and more vulnerable years, I was forced to read The Great Gatsby. As one of my first assignments in one of my first AP classes, I decided to show the strength of my dedication — by pulling up SparkNotes.

This tactic didn’t work for long, though, and eventually I did read the full novel. I tolerated it on my first read–through, enjoyed it on my second, and on my third, became totally obsessed as I realized that the narrator, Nick Carraway, was hopelessly in love with Gatsby.

Okay, while the canonicity of that may be debated, there’s no doubt that the novel has a layer of homoeroticism. The Great Gatsby has been dissected by scholars for decades — as a pessimistic examination of the American Dream, it naturally invites a plethora of interpretations.

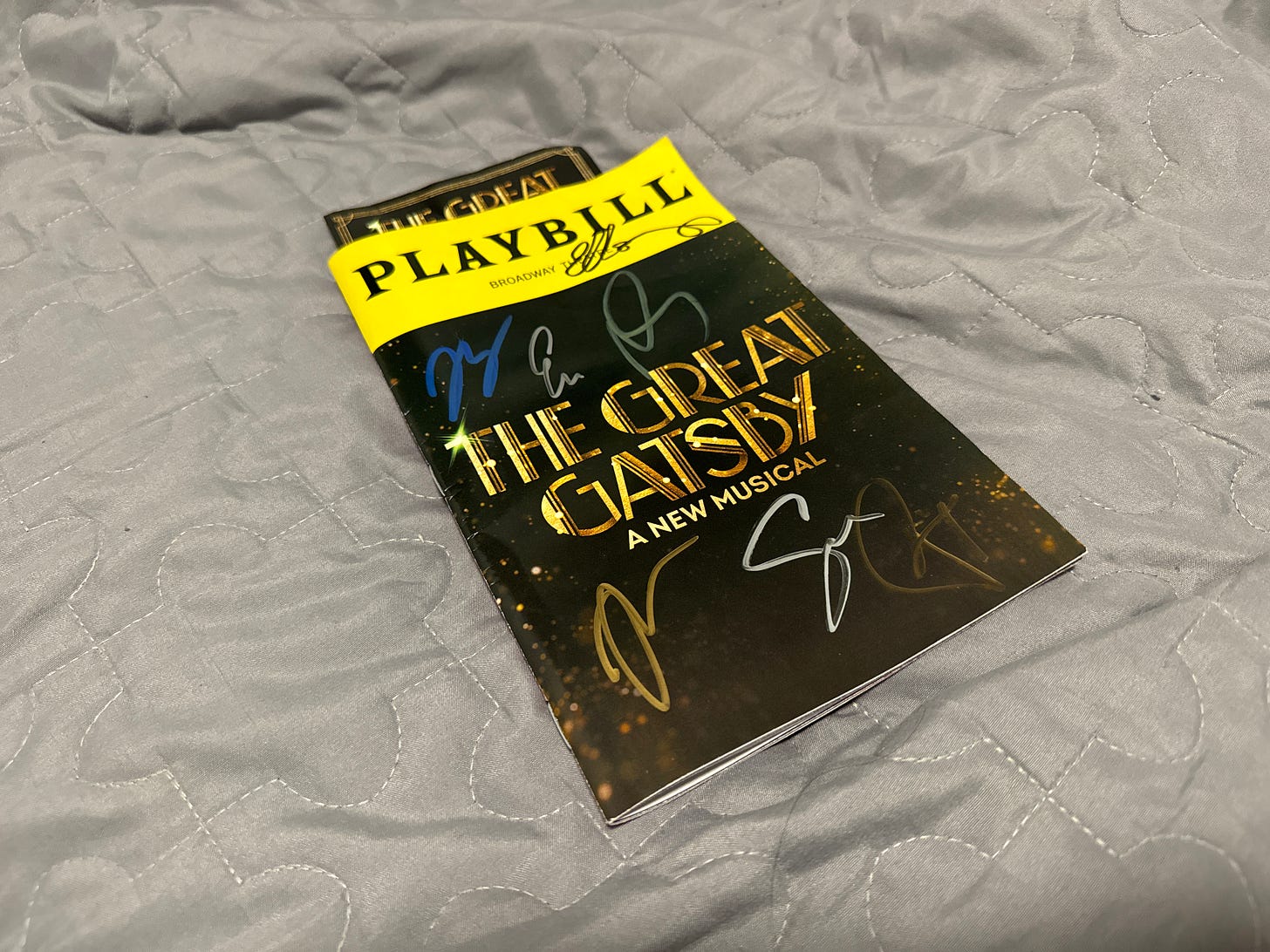

The most recent and prominent re-interpretation of The Great Gatsby found its way onto Broadway in April. After seeing Jeremy Jordan and Eva Noblezada on my “For You” page for months, my sister and I paid the show a visit. A hopeful start quickly took a turn for the worst as my (already low) expectations were crushed by what may be the blandest retelling of The Great Gatsby I’ve ever seen.

Waiting anxiously before the show…

Successful adaptations need an original drive, a fresh take on the source material that excuses its existence. The Great Gatsby on Broadway provides its fresh takes, but it does so in a way that fundamentally ignores the subtleties of the novel.

The musical is flashy and fun, with catchy choreography, a stellar cast, and impressive Tony award–winning costumes. The aesthetics are everything, from Nick’s cottage–core garden to Gatsby’s gaudy mansion and the Buchanans’ classic villa. The set features chandeliers, real cars, sparkling pyrotechnics, and more. It’s a display of grandeur so bold that, like Nick, I’m compelled to feel “simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

Jazz Age glamor may be a good way to market a Broadway show, but it doesn’t mesh well with The Great Gatsby’s melancholic tragedy. After all, the story ends with three people dying — including the title character — and the wealthy elite escaping without consequences. But unlike other tragic musicals like Les Misérables and Hadestown, The Great Gatsby does all it can to forget the story’s inherent tragedy, trading devastation for the easy mirage that Fitzgerald criticizes.

With deep dives into social class replaced by a Romeo–and–Juliet–style romance, queer–coded characters brought into an exuberant heterosexual relationship just to serve as a foil, and clear, easy–to–swallow morals, it’s understandable why this adaptation fails. The sticking point, for me, is Nick Carraway.

In the novel, Nick serves as the limited, first-person narrator. Some of the most interesting parts of The Great Gatsby are not what Nick writes, but what he chooses to leave out. His narration allows the audience to judge everyone else’s immorality, but also reveals his own, despite his belief in reserving judgment and honesty. Novel Nick is open–minded and morally flawed — he carries practically none of musical Nick’s outrage at Tom for cheating on Daisy, and most crucially, while musical Nick spends almost half the first act outraged at Gatsby for requesting to secretly meet with a married woman, novel Nick finds his demand “modest” and indubitably romantic.

By turning Nick from a biased narrator into a supporting character and a morally upright man, the musical removes a level of nuance from the tale. In the song “The Met,” Nick sings about wanting to indulge in NYC culture, such as visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while he’s instead surrounded by people who indulge in alcohol, sex, and 1920’s immorality. In the novel, Nick is judgemental yet fascinated by his new peers, and it’s implied he sleeps with a man in an era when homosexuality was still criminalized.

Going even further, the musical adaptation chose to explicitly create a romantic relationship between Jordan Baker and Nick, giving them couple dances, make–out sessions, and an almost marriage proposal. While the two were in a relationship in the novel, it was not the intense flare of passion like the musical. Nick explicitly states he was never in love with Jordan, merely curious and interested in her. Queer readings also point out that Nick describes Jordan in harshly masculine terms — not only does she play a male–dominated sport, she is compared to a “cadet,” has a “hard, jaunty body” and outside of her relationship with Nick, is really only seen around other women.

Got everyone’s signature except Jeremy Jordan!

While much of the queerness in The Great Gatsby is subtext, there’s plenty of textual themes that the musical glosses over.

The Great Gatsby also falls prey to Broadway’s notorious enthusiasm for color–blind casting, and this isn’t about realism. Noah Ricketts and Eva Noblezada play characters that were originally written as white (though, I admit I can’t imagine any other actor being able to do a better job than them) — and while there are plenty of stories where that wouldn’t matter, The Great Gatsby isn’t one of them. In the novel, Tom notoriously cites white supremacist propaganda, which Daisy mocks and Nick thinks of as “stale,” but the two characters are both implied to have racist beliefs. Nick’s narration certainly isn’t free from racialized language, and the “American Dream” he returns to at the end of the novel is one unreachable for many.

As someone who was also born and raised in the Midwest, I understand why Nick returns. But the Midwest novel Nick lived in is very different from the Midwest I lived in. The Great Gatsby musical doesn’t seem interested in addressing the novel’s themes of race and how race intersects with class, leaving out all explicit references to race beyond the unfortunate antisemitic tropes that Meyer Wolfsheim carries.

Take out the subtext, the explorations of social identities, and the death of the American Dream, and you’re left with failed star–crossed lovers and an interpersonal tragedy. If The Great Gatsby’s SparkNotes were all you read in school, then maybe you’ll enjoy this musical. But with mixed reviews coming from the American Repertory Theater’s Gatsby, it may be time to accept that Fitzgerald’s great American novel isn’t meant for the stage.