"American Born Chinese" and "Ms. Marvel": Sanitizing Asian American stories for a white audience

Why did I expect authentic and meaningful storytelling from Disney?

It’s May, which means when you log on to Disney+, one of the first things that pops up is their “Asian & Pacific Islander Stories” collection. Two of the top shows for action-fantasy fans like me are American Born Chinese and Ms. Marvel. The original American Born Chinese graphic novel and Ms. Marvel comics were a huge part of my elementary and middle school readings. I can’t even count the amount of times I’ve re-read both stories. Though I didn’t have the words to describe it back then, I know now that what drew me to them was the nuance and care that made it obvious that these stories were written by, and largely for, Asians.

The American Born Chinese graphic novel and Ms. Marvel comics are both meant to be read by middle schoolers. Thus, neither deal with themes that are too heavy — but both, obviously, deal with anti-Asian racism. Specifically, both stories feature a plotline where an Asian teenager uses a magic wish to turn into a white person.

In Ms. Marvel, the title character Kamala Khan wishes to be “beautiful, awesome, butt-kicking, and less complicated” like her idol: Carol Danvers aka Captain Marvel. She receives her wish and physically transforms into the image of Danvers, including the white skin and blond hair. In the third narrative of American Born Chinese, the main character Jin Wang is “so full of self-hatred” that he magically transforms into Danny, a white boy with blond hair.

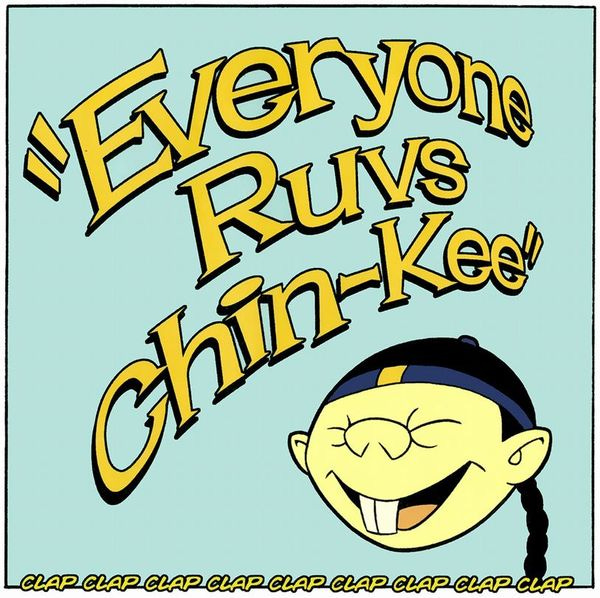

I admit the whole Chin-Kee narrative could not be put on screen without going through major adaptations.

With media literacy seemingly declining year by year, I can understand why creators would be hesitant to put these storylines to TV. Clips taken out of context and lack of understanding may cause people to believe that writers are advocating for internalized racism. But it’s truly unfortunate that American Born Chinese and Ms. Marvel chose to forgo these themes entirely, turning what could be a deep and meaningful discussion of racism in the U.S. into a shallow and performative check off the DEI checklist.

These stories — which were created by Asian artists — are beautiful works that carefully portray issues of identity and self-hatred that are true to the nature of experiencing racism. And that’s not just internalized racism from growing up in a dominant, oftentimes supremacist, culture, but subtle, modern nuances.

The Ms. Marvel comics make it clear that Kamala’s internalized racism and idolization of whiteness actively motivates many of her early decisions. When she meets one of her bullies before she learns to control her power, she instinctively assumes her “Carol Danvers” form, before reverting to her true appearance and admitting that her bully makes her “feel small.” The show, however, takes these moments away. The bully character still exists, but she’s not racist. And Kamala still idolizes Danvers, but her participation in the Captain Marvel cosplay competition is nothing like her physically assuming the body of a white woman because she can’t see herself as a superhero otherwise. The show also fails to explicitly address how 9/11 would have impacted Kamala and her family’s existence as a Muslim family in New Jersey, and uses a singular Islamophobic government agent to serve as the “bad apple” instead of addressing anything on a societal and institutional level.

Similarly, the American Born Chinese novel uses satire and three distinct narrative arcs to form Jin’s journey. The graphic novel focuses on Chinese myths, but is mostly centered in the slow, suburban bildungsroman plot. Jin grows up facing microaggressions like being accused of eating dog meat, and is determined to become “all-American.” In doing so, he destroys his friendships and almost loses himself, before the Monkey King — who is disguised as a racist Chinese caricature that could absolutely not be depicted on screens — shows him to embrace his identity. The TV show chooses to focus on flashy “Asian-ness” through a mythic-hero story that loses almost all legitimate discussions of institutional racism.

The problem is: a more accurate adaptation of American Born Chinese and Ms. Marvel would be very uncomfortable for a key audience demographic. But that was the point. These stories were written for all to understand, but not for all to relate.

In many of Disney’s adaptations, racism becomes a bargaining chip. The American Born Chinese graphic novel and Ms. Marvel comics were praised because they portrayed the effects of racism from the perspective of the ones who suffer from it. The TV shows instead address racism in such a passive manner that it does nothing but appease the white gaze.

Maybe I’m being pessimistic. I’m well aware that these shows are no longer aimed to me as a target audience, and that racism in the U.S. has changed even in the few years it’s been since I was a middle schooler. Sana Amanat, the creator of Ms. Marvel, said she hoped the character would provide crucial representation that would help the next generation not experience identity rejection as she did. But Amanat also said: “At the end of the day, me embracing my identity…does not mean (I’m) denying their identity. It’s about me. And it’s the story that I wanna tell. Everyone should have the right to tell their own story.”

The American Born Chinese and Ms. Marvel shows are a lighthearted and fun watch, and a great addition to Disney+. At the end of the day, though, the seemingly-intentional mishandling of racism to appease the broader audience adds little to authentic and engaging Asian American storytelling, instead becoming another cog in the commodification wheel of the TV industry.